Arts

Tharu printmaking finds life in rituals

For generations, the Tharu have practised a quiet, enduring form of printmaking—one rooted not in studios, but in kitchens, courtyards, and rituals.

Aarya Chand

Printmaking (Chappai Kala) on the walls and agricultural tools has been a tradition passed down through generations in the southern plains of Nepal, mainly in villages bordering the Tarai’s forests and rivers. It is done on doorways, in kitchen storerooms, and the pressed ridges of a thekua (a deep-fried sweet snack made from wheat flour). For generations, the Tharu community has practised a form of printmaking that doesn’t claim galleries or museums but lives instead in rituals, festivals, and the quiet repetition of domestic life.

Manu Kumar Chaudhary, a young visual artist and recent fine art graduate from Kathmandu University who also wrote a thesis on printmaking in the Tharu community, speaks of this with a mixture of reverence and reflection. “When I started studying printmaking, I realised we already had it in our culture: woodblock impressions, thumb prints, palm printing. It wasn’t new to us; it was just unnamed,” he says.

Unlike the techniques popularised in Europe or Japan, Tharu printmaking isn’t centred on paper or limited to the studio. It emerges through rituals like thapa marne—handprint impressions made during Tihar—and the crafting of food offerings like thekua, shaped using carved wooden moulds called agrautai. These are not just aesthetic choices but expressions of lineage and locality.

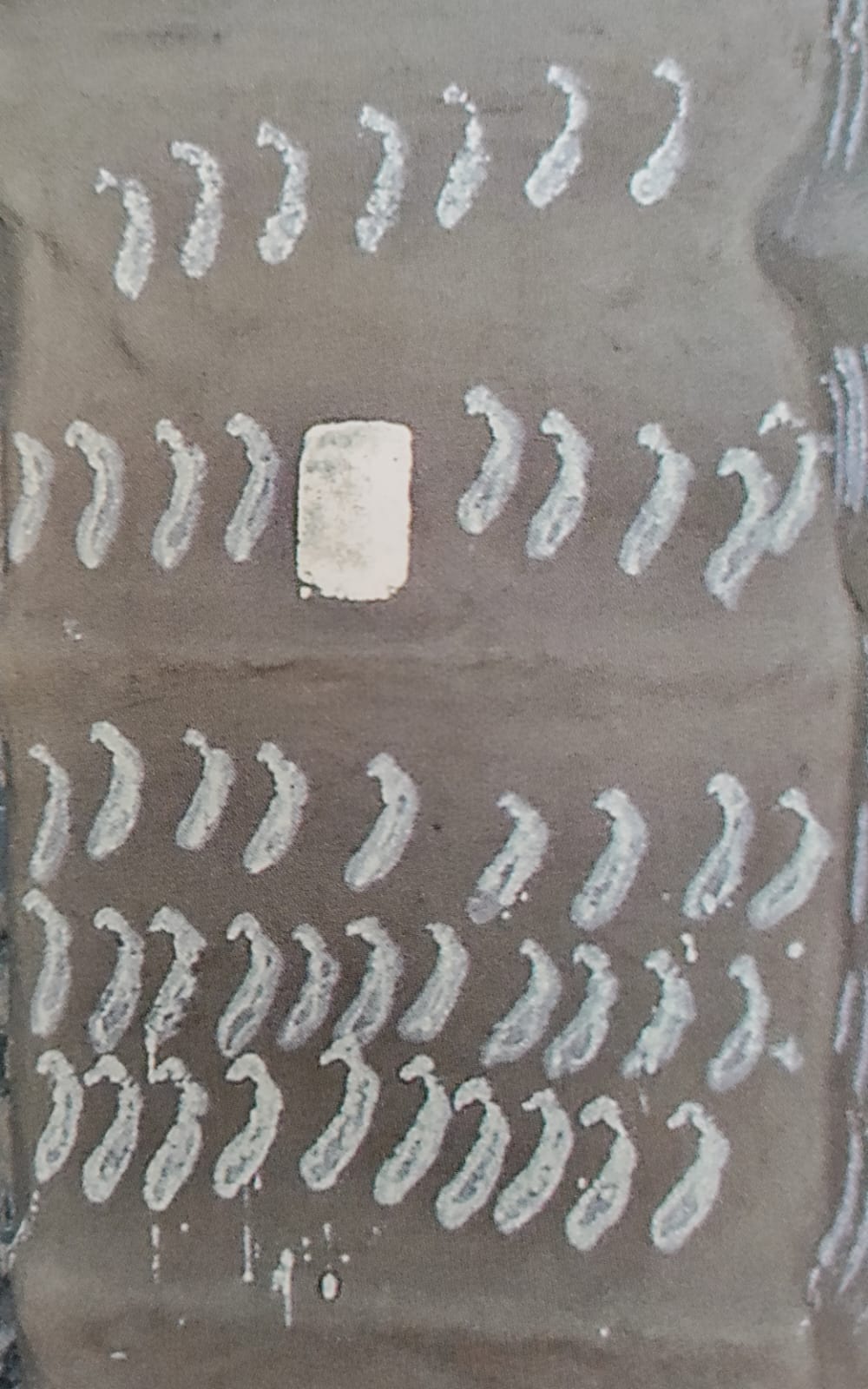

In the Tharu calendar, printmaking appears seasonally, much like the crops their lives depend on. During Chhath, women press the rich brown dough of thekua into intricately carved wooden blocks. These are not merely tools for shaping food—they are carriers of designs derived from local flora and fauna: the curve of a fish, the bloom of a hibiscus, the sun’s circle.

“The thekua moulds are usually made from durable woods like sakhua or sissoo,” says Chaudhary. “They resist rain and hold their carvings well.

During Tihar, another ritual unfolds. On Sohraiya, the day following Gobardhan Puja, Tharu families clean their farming tools, wash their oxen, and oil the wooden doors of their homes. Then they begin to print.

A mixture of rice flour and water is prepared to create a paste. Palms are dipped into this slurry and pressed onto walls, gates, and tools—creating thapa, the handprints of the Tharu. “Seven handprints are made on a wall to symbolise the goddess Laxmi,” Chaudhary explains. “We place a red tika at the centre of the palm print. It’s our way of honouring the tools and animals that help us live.’’

Sanjib Chaudhary, a cultural researcher, notes that these print practices are embedded in the everyday. “You’ll see these prints on grain storage containers, on the bodies of animals, on the walls of homes,” he says. ‘‘They’re made with what’s at hand—carved into bottle gourds, or applied with fingers. The aesthetic is flat, linear, and always local.”

In eastern Tharu regions, coconut trees and peacocks are more common; in the west, monkeys and karam trees appear in carvings. Despite the regional variations, the art shares a visual grammar: repetition, symmetry, and connection to land. “Even when there’s no compass, we use rope to mark circles, which become triangles and other patterns,” says Sanjib. “It’s a craft of resourcefulness,” he adds. Some motifs have ceremonial value, while others are simply decorative.

In some households, old treasure boxes carry faded impressions of earlier prints. In others, the wooden blocks that shape food are passed down like heirlooms. Elder community members recall pressing dough into these carved moulds since childhood. Nagjyoti Devi Tharuni from Parsa district says, “I don't remember when we started. It has always been there. The blocks carry the hands of our mothers and grandmothers.”

For Gujeswori Devi Tharuni, now in her eighties, the carving of blocks was a craft of necessity and skill. “The woods we used: sal, sakhuwa, karam—were strong. The designs came from our surroundings. What we saw, we carved. We used to make these ourselves or buy them in the market if we couldn’t,” she shares.

The visual language—fish, flowers, peacocks, suns, the five-petal Asian abutilon flower—is rooted in the Tharu’s interaction with nature and agriculture. “The abutilon is a five-petal shape that can be made using two fingers in sequence, and it is the most common design. Even without formal tools, Tharu artists developed forms that were efficient, beautiful, and symbolic.”

There’s also a tactile intimacy to the process. In some villages, children cut the tops off bottle gourds, carve patterns into the pulp, dip them in natural dyes, and print them on cattle hides. The action is playful, but the meaning is not frivolous. “It’s about connection,” says Manu. “Between people, humans and animals, us and the land.”

Art educator and textile designer Prabha Napit reflects on these traditions with quiet caution. “Mass imports from India have eclipsed traditional block printing in Nepal,” she says. “When everything is available cheaper, faster, cleaner, people forget the value of what takes time.”

Napit, who teaches at Kathmandu University, grew up in a neighbourhood of Chitrakar and Ranjitkar communities, where woodblock carving was once a primary trade. “I’ve seen blocks from the 1980s in my home,” she says. “Today’s blocks are lighter, cheaper. The older ones were heavier, red-brown in colour, with fine detail. You can’t find that quality now.”

She believes one reason for the decline in traditional printmaking is the reluctance to share. “Older generations kept the craft close. They feared losing their market. And so the knowledge died with them.”

The erosion is more subtle but no less real for the Tharu community. “Younger people hesitate to embrace it,” Manu notes. “They associate printmaking with village life, not art. He points to the godhana tattoos—done with neem thorns and soot—that have mostly disappeared. People want modern tattoos now.”

Even within rituals, the gestures have become thinner. “Some youths feel shy about putting prints on their walls,” Manu says. “Before marriage, women would get tattoos to show their womanhood. Now, that practice is nearly gone.”

Despite this fading, Manu sees potential in bridging traditional and contemporary practices. “In the city, we work on etching and zinc plates. In the village, it’s woodblocks and slurry paste. But the content—the stories, the motifs—remains the same,” he says.

Sanjib echoes the sentiment. “These traditions will change. That’s natural. But understanding their roots allows us to grow in meaningful directions.”

For Napit, revival doesn’t mean romanticising the past. “You don’t need to preserve every technique,” she says. “But you do need to understand it. That’s how you create responsibly.”

As more artists like Manu integrate Tharu printmaking into their formal work, the line between ritual and art becomes thinner. In his recent projects, he has experimented with adapting thekua blocks into contemporary prints and using natural dyes in city-based studios.

“I want our people to see these as art forms, not just customs,” he says. “When you respect your culture, you protect your identity.”

Traditional printmaking in the Tharu community is not a static practice etched in museum glass. Instead, it is a living form that flickers in kitchen corners during Chhath, glows on mud walls during Tihar, and imprints itself on the hearts of those who practice it.

Whether in a palm print on a plough, a pressed thekua shared in prayer, or a woodblock carved in memory of a flower, these impressions are part of a lineage. They ask not to be glorified, but simply acknowledged.

As Manu puts it, “This isn’t just about saving a tradition. It’s about remembering where we come from. And pressing that memory, repeatedly, into the surface of daily life.”

22.39°C Kathmandu

22.39°C Kathmandu